PEDRO OLIVEIRA: YOU STILL LOVE ME?

“You still love me?” The sentence appears within the landscape like a fragile light. It feels almost out of place, too simple, too exposed. And yet it contains everything. A child’s question, an adult’s question. A question never asked of a father, often asked of love. It opens Pedro Oliveira’s project at its most intimate level: doubt, the need for recognition, the fear of not being enough.

The painting begins here, in this fracture.

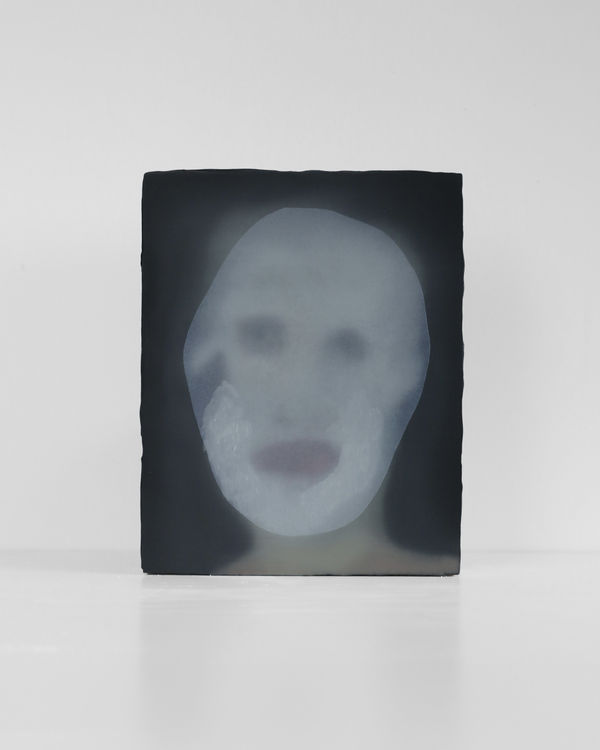

For several years, Pedro Oliveira has developed a body of work in which memory is never stable material. His images emerge from old photographs, personal experiences, and persistent mental images. They do not attempt to reconstruct the past. Instead, they explore how memory transforms what it preserves. The image is never fixed; it is always in the process of forming or dissolving.

The pictorial process follows this movement. Thin layers, translucent superimpositions, successive erasures: the surface becomes a site of gradual appearance. Painting acts as a mental filter. It records the distance between what was lived and what is retained.

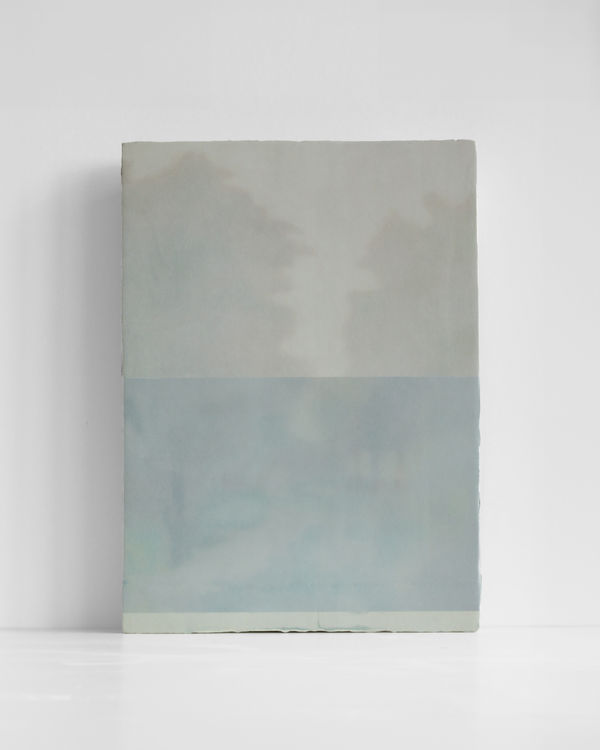

In the exhibition at Galerie Prima, landscapes occupy a central place. They are not identifiable locations but projections. “They are imaginary places, hidden behind a white that does not erase, but makes them impossible to reach.” This white is fundamental.

While reading Portugal, Today: The Fear of Existing by José Gil, Pedro Oliveira was drawn to the notion of the “white shadow.” The philosopher seeks to understand why certain collective experiences never fully inscribe themselves in reality. Events take place, yet they seem to dissolve before producing conflict or rupture. This difficulty in “existing” does not stem from violent censorship or dark obscurity, but from a diffuse suspension. To explain this, Gil turns to perception itself. He speaks of an “invisible unconscious texture.” The world never appears to us with absolute clarity.

In Pedro Oliveira’s work, this white shadow becomes pictorial. The luminous veil crossing the landscapes does not conceal the world. “In my interpretation, the white shadow becomes a white veil, the effect of an excess of light that makes it difficult to see what stands before us.” Here, light does not illuminate more clearly; it makes perception uncertain, as if painting were exposing the very condition of seeing.

This tension also runs through the works in which the motif of the birthday cake appears. An ordinary, almost banal subject, it returns repeatedly, always similar yet never identical. “Memories change over time: sometimes they are good, sometimes they are bad, and sometimes we recall them differently.” Each painting is a variation, an attempt to stabilize an image that keeps slipping away.

Repetition does not produce certainty but heightened instability. We think we recognize the scene, then it escapes us. The image becomes uncertain, as if memory itself were hesitating. Ultimately, he writes, there would remain “only one image,” the result of superimposed layers where memory, projection, and perception coexist. This idea runs throughout the exhibition. The paintings are not scenes to be read; they are mental spaces where several temporalities condense.

Pedro Oliveira’s paintings require a slow and attentive gaze. As in the work of Gerhard Richter or in certain landscapes by Tarkovsky, the real and the unreal coexist. Painting becomes a space of suspension — where personal history meets a broader reflection on identity, filiation, love, and memory.

In the midst of this white veil, one question persists.

“You still love me?”